I’d watched Shudder’s Horror Noire documentary back in 2019, and it introduced me to many films I’d heard about, and some that I did not.

For instance, Ganja & Hess was one of the movies I’d never heard about: this experimental, almost lyrical dreamlike piece about vampires made by the Black filmmaker Bill Gunn and starring Duane Jones from Night of the Living Dead fame. And then I also got around to watching Candyman, and while I still love Clive Barker’s “The Forbidden,” Tony Todd brought him to life in a whole other way that I’m glad I got myself to see. I was never a true horror fanatic, and all the permutations, and so I came into looking at some of these films starring Black actors, and created by Black filmmakers from a fresh perspective: looking at art that I wouldn’t have considered back when I was younger. Certainly Jordan Peele’s Get Out and Us helped me along the way to this fascination, with both the dread of seeing how racism would be incorporated into horror – especially from the relationship dynamic of the former film – and the pacing and fine social commentary inherent in both.

And then, you have Blacula.

I admit: I would have slept on it in my old, dark, subterranean coffin if it hadn’t been for Horror Noire. I’d heard of it in passing, along with a ton of other Blaxploitation films of the seventies, and had my preconceptions about what they – and it – would be like. Just as I feared Get Out and watching someone from outside a family background get his humanity and freedom taken away – the notion guest-friendship turned into a thin veneer to cover a distrust and injury of the outsider and knowing he will always be so in certain places, which has overlap with me on a personal level that I might go into in another post – I was thought something by the name of Blacula would take that racism to the nth degree and make a spectacle of it.

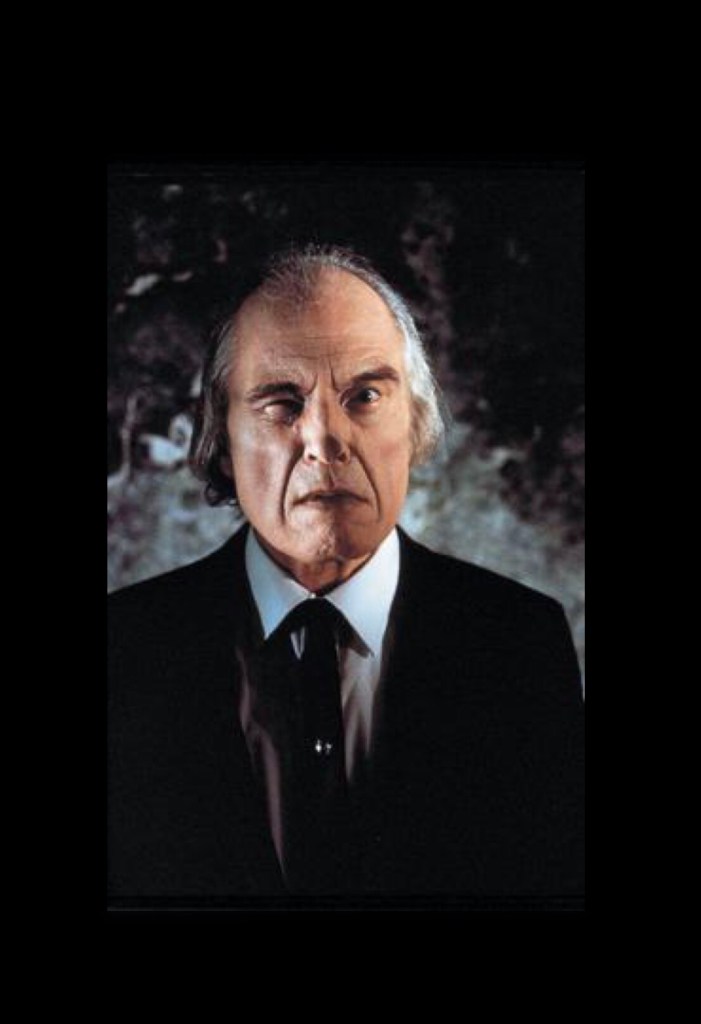

A little while back, I was saying to someone that if Get Out had been created by anyone other than Jordan Peele with his understanding of pacing and punchlines, the brain transplant element would have been what it’s always been portrayed as in popular culture: a B movie curiosity at best, with little contemporary fear, or resonance, involved. But Get Out had Jordan Peele and his crew, and Blacula had William Crain, and William Marshall.

Imagine a man and his consort sent by their elders to stop the slave trade in their land, perhaps even on the entire African continent, and they go to a powerful European statesman: who happens to be Dracula. Consider the man, a prince of his people, urbane and educated watching as this fiend turns him into a monster – infecting him with his own systemic imperialist and white supremacist curse – and locking him into a coffin for over two centuries while his consort starves to death helplessly next to him. He is named by this elder monstrosity, derisively, Blacula. Perhaps that’s a bit of a stretch given that they are in Transylvania and they would be speaking in Romanian, or possibly Latin as nobility, but this is entertainment and English is the accessible language of most films from America. But with that aside, just think about this prince waking up, having only the hunger, being in an alien land and world, finding the person who seems to be the reincarnation of the woman who died separated from him by a box, creating other monsters from needing to feed, losing her again, and then taking his own life when he realizes he’s pretty much done.

That is Blacula. And it is a good movie. I like that William Marshall, who plays him, named the vampire Mamuwalde and gave him the entire backstory of having come from the Abani Tribe – while smacking of some exoticism – making him his own character independent of Dracula, and giving him a whole other world as his foundation. It isn’t perfect. Certainly the homophobia directed towards the gay couple – Bobby McCoy and Billy Schaffer – by both Mamuwalde in casually killing them when they release him, and even his eventual hunter the L.A. Police Scientific Division specialist Dr. Gordon Thomas calling them a derogatory term is something other reviewers, such as Kevelis Matthews-Alvarado in her guest post on Horror Homeroom Blacula (1972): Flawed But Important, have pointed out, and criticized. Those sentiments were a part of the seventies, of course, especially amongst the higher echelons of that society and the police that guard it.

I read a few articles on Blacula after I saw the first film, and there were a few in particular that focused on how he became a vessel for the racist white heterosexual hegemony’s or kyriarchy’s demonization of women, and other minorities. Daisy Howarth, in her essay Monster to Hero: Evolving Perceptions of Black Characterization within the Horror Genre, focuses both on Get Out and Blacula: and particularly on Mamuwalde embodying a “black hypermasculinity” to compensate for being enslaved or having racist white European prejudices internalized into his very being. Howarth also makes a comment about Mamuwalde reflecting a critique of a facet of Black 1970s counter-culture when she states that his “victims tend to be those that compromise his masculinity, which seems to be an advertence towards an effort to regain a form of power, whether that be over women in dominant positions or homosexual black males. The expectation of macho masculinity is also reflected through the Black Panther movement of the 1970’s that sought for a ‘discourse of recovering Black manhood’, and thus Blacula’s choice of victims emphasises his pursuit to become less of a monster and more of a man.” The fact that a powerful movement like the Black Panthers had issues with the white-controlled police, but also dealt with internal politics and gender issues is an interesting parallel with how Mamuwalde deals with the first gay couple – the first interracial couple defying the patriarchal system to which is implicit in his blood now, as kinkedsista points out in their Blog post “Blacula”: A Commentary on Vampirism, Slavery and Black Male Identity.

Kinkedsista’s article, specifically, is one of the first works I’d read on Blacula immediately after watching it the first time. She examines further how Mamuwalde was already affected by European biases when she looks at how he is European-educated and dressed in a Western style, compared to his consort Luva who is dressed in the aesthetics of their people the Abani, or the Ibani Tribe. Matthews-Alvarado mentions in her article that the Africa – or African group – described in Blacula is fairly exoticized, even perhaps Orientalized: and that by telling Tina Williams that they had come from a Tribe of hunters, along with his bestial appearane when he needs to feed, it hearkens back to some “primitive” imagery. So again, we have Mamuwalde as embodying a force of European imperialism, and the racist stereotype of “the beast or the savage.”

At the same time, as Howarth explains with regards to Tina Williams’ – the seemingly reincarnated Luva – struggles, Mamuwalde represents an idealized link back to a culture from which Black Americans had been separately from – by force, and time. She states “In this sense, the duality of being living and dead or monster and lover, forms a disparity that reflects on the greater issue of being black and American. Therefore, if Tina chooses to pursue her love for Blacula she must also choose between existing in ‘a compromised contemporary black community’ and ‘an African idealised civilisation of the past’. In order to obtain a sense of her lost heritage Tina must enslave herself to Blacula and thus ideologically she can no longer be both contemporary woman and inherently black, highlighting a struggle to obtain black pride in 1970’s America.”

It is an interesting counterpoint to the vampires that Mamuwalde creates as a result of simply feeding on victims – not even purposefully creating them – perhaps another subversive look at racist views, sometimes internalized, of male Black virility or hypersexuality. They are ashen, discoloured, and twisted. Chris Alexander, in his article The Beauty of Blacula, states that William Crain “gives his black vampires a powder white sheen that makes them look authentically ghost-like but also adds an odd, disturbing reverse-minstrel aesthetic, as if the characters have to turn into “whitey” to exemplify their evil. This device is likely accidental, but that’s irrelevant. It’s there. And when those ghouls go for their prey, they run screaming in slow-motion. their fangs bared, like banshees from the pits of Hell.” In retrospect, their aesthetic is reminiscent to that of the undead in Sisworo Gautama Putra’s 1980 film Pengabdi Setan, or Satan’s Slave, which have ties to Indonesia’s pontianak myth: making me wonder if there was some creative influence, or if this is a case people drawing on their own folklore, or stereotypes to take “internalized evil” and make it overt for the sake of creating a statement: or using what they have in their cultural consciousness.

Mamuwalde’s vampires are more earthly and far less ethereal or ghostly than they appear. They can eat food, and drink wine. They can even have sex. By the film sequel Scream, Blacula Scream, directed by Bob Kelljan, it’s also possible they can make themselves look more human by drinking a large amount of human blood. They can’t see themselves on a reflective surface. Crosses seem to repel them. And they can be killed by a stake through the heart, or exposure to sunlight: that doesn’t so much turn them into ashes, as it just renders them deceased, with the exception of Mamuwalde himself possibly due to his advanced age. Mamuwalde is the only one who can shapeshift into a bat, and from what we see in both films he has the power to compel his creations to do what he wants and, when doesn’t, they generally go on a mindless feeding spree and multiply. But what is also interesting is that he has the power of mesmerism or fixation: and some of his creations do as well, mainly the friend of Lisa Fortier in the sequel from which he feeds. Yet Mamuwalde himself can communicate telepathically with Tina, though it might have something to do with her being Luva’s reincarnation, and a possible bond between them.

Mamuwalde’s vampires are more earthly and far less ethereal or ghostly than they appear. They can eat food, and drink wine. They can even have sex. By the film sequel Scream, Blacula Scream, directed by Bob Kelljan, it’s also possible they can make themselves look more human by drinking a large amount of human blood. They can’t see themselves on a reflective surface. Crosses seem to repel them. And they can be killed by a stake through the heart, or exposure to sunlight: that doesn’t so much turn them into ashes, as it just renders them deceased, with the exception of Mamuwalde himself possibly due to his advanced age. Mamuwalde is the only one who can shapeshift into a bat, and from what we see in both films he has the power to compel his creations to do what he wants and, when doesn’t, they generally go on a mindless feeding spree and multiply. But what is also interesting is that he has the power of mesmerism or fixation: and some of his creations do as well, mainly the friend of Lisa Fortier in the sequel from which he feeds. Yet Mamuwalde himself can communicate telepathically with Tina, though it might have something to do with her being Luva’s reincarnation, and a possible bond between them.

So now we are the crux of it. I was surprised at how good, and compact, Blacula actually is as a film. The heroes, or hunters, are refreshingly intelligent. When Dr. Thomas wants to prove that vampires exist, after researching them extensively first, to his girlfriend and coworker Michelle Williams, and then his colleague Police Lieutenant Jack Peters, he uncovers Mamuwalde’s corpses: to let their actions speak for themselves. Mamuwalde himself outsmarts the LAPD and Thomas by luring them to his hideout, only to have his vampires waiting for them: including one who is on the police force, and hiding in plain sight. We’ve mentioned the aesthetics of the vampires as well, and honestly? Mamuwalde’s charm as portrayed by Marshall Williams: his intelligence, gravitas, and tormented state go a long way to selling this character with such a ridiculous and exploitatively insulting moniker like Blacula. His relationship with Tina, that ephemeral, beautiful, unexplained bond is portrayed well and how he reconnects with her after initially terrifying the hell out of her is clever. And that ending: where he loses her again, and he decides to go meet the sunrise is haunting and poignant. The hunters don’t kill him. The white-owned police don’t destroy him. It’s only at the end, when his reason to seriously exist, is gone – when his own arrogance and violence from the curse on himself thwarts his ambitions in addition to the death of Tina, that he decides he’s finished, and he faces his fear in the sun: to die.

And there is the sequel I mentioned, Scream, Blacula Scream.

I almost didn’t watch this one, given how well the first film ended. But it had elements that intrigued me. So imagine the plot beats to the first film by Crain, except Bob Kelljan and the writers Joan Torres, Raymond Koenig, and Maurice Jules add a voodoo element and a coven family rivalry into the mix. You have Lisa Fortier, played by the amazing Pam Grier, who seems to be the love interest of this film. And then you have her boyfriend Justin Carter – a former LA policeman and African antiquities collector – who starts investigating vampires after Mamuwalde comes back into the scene, and he has to convince his former white colleague, or boss, Lieutenant Harley Dunlop, that they are dealing with vampires.

Lisa’s foster brother, Willis Daniels, is passed over as head of the voodoo coven after his mother – the previous leader and voodoo queen – dies. He tries to get revenge, and take power from Lisa by using a dark ritual to resurrect Mamuwalde from the bones he’s left behind from the previous movie when he committed enthunasia on himself. It doesn’t go well for Willis because, although we never see Mamuwalde reform or come back, he comes out of the room and converts Willis to one of his undead servants. And for all of Willis’ and his girlfriend’s seeming humanity even after all of that, Mamuwalde has no chill, and he immediately can take control of them whenever he wants, and is not above threatening their existences.

Mamuwalde also hunts some of Lisa’s friends, as he did Tina’s. He has a bond with Lisa, but she isn’t Luva’s reincarnation as these events seemingly happen a year after the first film. However, because she is a natural practitioner of her art, he hopes she can use sympathetic magic to “purge the curse” from inside him, and let him become mortal again so he can return to his people … somehow. Of course, despite all the vampire minions he has, Lisa’s boyfriend and his police friends interfere, the ritual is interrupted, and Mamuwalde finally loses it. He embraces his vampire slave name Blacula out of pure spite, giving up on his humanity, kills a lot of people by throwing them awkwardly into walls, and Lisa stops him with a voodoo doll she made of him: though what ultimately happens to Mamuwalde after this remains ambiguous as it doesn’t seem to have died … again.

So what it comes down to, for me, is which is the stronger film?

Right. I prefer the first one. Blacula is tight. It has a premise, an engaging fixation for Mamuwalde, a fascinating series of interactions, some terrifying sequences, and a tragic but fitting end where Mamuwalde finally realizes that his actions are almost as culpable as those of his foes, and ends himself. Scream, Blacula, Scream is a bit more disjointed, repeating quite a few plot points of the first film, somehow set in the same city with different characters and no one remembering what happened a year ago, and skimping on some special effects like Mamuwalde reforming from some charred bones in an arcane ritual.

However …

The fact that Mamuwalde is far more vicious makes sense when you realize the peace of death was stolen from him by some young, idiot upstart. His torment of Willis is so much clearer in that light when you consider what he took from him. His disgust over his creations is a projection of his own self-hatred, and it is the thing of which he wants Lisa to help him be rid. I do think the whole Lisa and Willis rivalry element should have been played out more, or at least have Willis and Justin – who hate each other – have one last fight. But rendering that boastful, arrogant, overcompensating Willis into a broken slave has its own resonance too. And seeing Mamuwalde’s own evil come back to roost does have some beats on its own. How can he redeem himself, or be redeemed, if he took so many lives, and controlled them for his own benefit? What ritual could rid him of that? Even so, as Gregory Day points out amongst other elements in his article Blaxploitation Cinema: ‘Blacula’ / ‘Scream, Blacula, Scream’

I love how Maumwalde confronts some pimps about using their “sisters” as slaves in imitation of “their masters,” and doesn’t – or perhaps doesn’t want to – see the mirror image of himself in them as he makes his own thralls. I do really wish they’d kept his silver-inlined cloak as opposed to simply giving him the whole red lining of Dracula. I mean, we know he has ties to Dracula. If the flashback sequences weren’t enough, we saw this in the first film. Calm down, merchandising department.

But I think it’s his relation to Lisa Fortier that does it. Pam Grier is a popular actress in and of herself, but her character represents something interesting in everything about which we’ve been talking. Voodoo, or perhaps elements of it, has West African traditions combined with Catholicism – or Christianity – due to the slaves being taken from that region and being forced to convert by their enslavers. Voodoo, or vodoun, isn’t always Christian-influenced but the fact that both Lisa and Willis speak French when performing their rituals seems to illustrate that some Creole or other influence came into these rites: either from colonized West Africa, or in America itself. And the way that Lisa starts to seemingly purge the evil out of Mamuwalde is reminiscent, and we go back to the start here, of Ganja & Hess: where the vampires of that world can only find peace – in this case death – through prayer, and sitting under the shadow of a cross. Ganja & Hess had been released in 1973, while Blacula and Scream Blacula Scream had come out in 1972 and 1973 again respectively. I also, though, like the idea that voodoo in this world is its own power, and affects vampires and people differently despite any links it may or may not have to other religions or spiritual systems.

Yet here is what gets me. In light of Matthews-Alvarado, Howarth and kinkedsista’s articles, and their observations of black hypermasculinity, and European influences, and a Black woman’s place in those dynamics, we find a complete opposite to what finally stops Mamuwalde: as, you know, it is the last film in the series so far since the 1970s. Lisa Fortier is a Black woman in touch with her spirituality — her roots — just like her boyfriend. The police target her group specifically, especially, the racist Dunlop who is far less sympathetic than Blacula’s Jack Peters, and defies them when they try to pin Mamuwalde’s murders of her coven. And unlike Tina who is killed because she let herself get drawn into Mamuwalde’s cycle, and the female cab driver Juanita Jones who dies because she insullts him by calling him “boy” and has no choice at all in what she becomes, Lisa is a powerful Black woman who chooses her contemporary world over Mamuwalde’s exoticized past and the infection of European racist slavery that he offers. It pains her to do it, to hurt this wounded man, a great man made a slave and part of a vicious cycle of subjugation and a treasure trove of Black history and culture – who came to her for help before giving up, and into his worst nature. He is literally going to punish Justin the way that Dracula did him: perpetuating the cycle by infecting another intelligent and educated Black man with systemic racism. And Lisa stops that in its tracks with her ties to the traditions of the past, and the power of the present: of her own mindfulness and love for a better future. She does what she does allow herself, her loved ones, and her own life to survive.

In the end, I think Blacula was a better movie but Scream Blacula Scream, while as Chris Alexander put it, was about his victims, had a better message. Even so, Pam Grier’s quiet but fierce performance notwithstanding, Blacula is my favourite of the two. As of this writing, there is currently work on a reboot to the series. And I’d like it to focus more on Mamuwalde’s character development, and that of the other characters: perhaps in a retelling in the ‘70s or ‘90s, or even in the aughts. I can only hope that whatever they make, it will capture the grandiosity of Marshall’s character, and apply the message of both films to this time because, like poor Mamuwalde, suspended between life and death, motion and stillness, hunger and despair, the enemies outside and the ones they put within, it is timeless.